Proboscidea is

the order of mammals with trunks, and their more primitive relatives

with “proto-trunks”. Today the only living members of this order

are in the family Elephantidae, the

living Asian, African savannah and forest elephants. These are

magnificent megafauna in themselves, treasures of any zoo which has

them, butchered for their incisors and occasionally used in human

warfare. But there is much more to Proboscidea than

the living elephants as this order has a total of around 164 mostly

extinct species, which diversified into all sorts of bizarre forms,

such as the four tusked deinotheres and the shovel-tusked

Platybelodon. These

fantastical, mighty beasts are only known to us through the fossil

record. It is tempting to compare the largest Proboscideans, to the

herbivorous dinosaurs, especially the sauropods, as they fill the

niche for large browsing animal. I have no chance of discussing all

these species here, but I will mention some of the most outlandish

and interesting Proboscideans less familiar to us than elephants and

mammoths.

Animals

with 3m long teeth don't drop out of the sky, they as an order have a

history stretching back into the Paleocene, starting with an

apparently humble creature the size of a rabbit. The evolutionary

process basically involves a gradual increase in body size, growth of

tusks and size of head. The heavy tusked head could not be supported

by a long neck, and as their legs were long they could not reach the

ground with their mouth to eat and drink. This problem was “solved”

by the elongation of the muscular nasal cavity, forming a trunk.

These processes were not so smooth and continuous, and the journey

had many turns from this path.

A reconstruction of Eritherium.

One

of the earliest Proboscidean is Eritherium

which lived 60 million years ago, the remains of this creature

was first found in phosphate deposits in Morocco in 2012. The

Eritherium remains show no sign of a trunk, which is formed by

the evolutionary fusion of upper lip and nostril, which would be

evident in an enlarged naval cavity. It is a Proboscidean without a

proboscis, but probably had a very mobile upper lip, a little like

the unrelated tapirs. So what makes this animal a Proboscidean? A

number of features which were elaborated in later Proboscideans are

present in Eritherium, including enlarged incisors, which

would eventually sprout forth to create tusks, and simple lophodont

molars (molars with ridges perpendicular to the jaw line). It was 5kg

in weight, but this outweighs most other Paleocene mammals, many of

which were decided shrew-like. Eritherium was probably

somewhat aquatic, like many of the Proboscideans including the swamp

dwelling American Mastodon and modern elephants who use their trunks

as “snorkels” in order to swim up to 48km offshore. It

is likely that the common ancestor of Proboscideans, Sirenians (sea

cows) and the extinct Desmostylia were fully aquatic.

A reconstruction of Phiomia

A

later group of Proboscideans is Phiomia, a

direct relative of modern elephants, which lived between 35

and 25 million years ago. This was a larger animal, 2m high at the

shoulder. Remains show evidence of a short rudimentary trunk (based

on the larger nasal cavity) and enlarged incisors on the lower and

upper jaws, meaning it had two pairs of tusks. Tusks are simply

enlarged incisors, about a third of it's length, the pulp cavity, is

embedded in the skull. The visible tusk is the ivory made of dentine

covered by enamel. After it has shed it's milk tusks a Proboscidean

maintains and grows it's tusks throughout it's life. In observed

species the male has the longest tusks, as befitting their primary

use in fighting, but they are and were also used to strip bark,

defend from predators and in species like the woolly mammoth they may

have been used to break up ice to find food.

A skull of Deinotherium at the Natural History Museum

The

branches of evolutionary tree which did not lead to elephants contain

more baroque Proboscideans, including two groups which lived at

approximately the same time, Deinotherium and

Platybelodon. The skull of Deinotherium is

a disturbing thing to bump into in a museum, no doubt horrifying for

an ancient person, with no ideas about deep time, to find in the

wild. The skull appears to have two horns curved backwards out of

it's chin, like a demonic beard presumably used for gouging. If an

ancient person who expects all animals to have forward facing eyes

like they do, sees the enlarged nasal cavity at the front of the

skull, it could be mistaken for the skull of a monster. Indeed, the

ancient myths of the Cyclops could be inspired by the discovery of

Proboscidean fossils in Greece. Deinotherium itself lost it's

upper pair of tusks and maintained the lower tusks (the opposite of

modern elephants). As you can tell from a reconstruction of these

creatures, the lower tusks hid quite discretely under the trunk which

filled the nasal cavity at the front of the animals head, making it

look less horrifying. They were quite primitive, lacking the

sequential teeth eruption of later Proboscideans.

The

skull of Deinotherium is a disturbing thing to

bump into in a museum and no doubt horrifying for an ancient person,

with no ideas about deep time, to find in the wild. The skull appears

to have two horns curved backwards from it chin, like a monstrous

beard, used for gouging. Indeed, the ancient myths of the Cyclops

could be inspired by the discovery of Proboscidean fossils in Greece,

due to the fused external naris resembling an eye socket. Even the

name Deinotherium is from the Greek for “terrible beast”.

In reality, Deinotherium lost it's upper tusks and maintained

it's lower tusks (the opposite of modern elephants), and probably

used these curved tusks to scrap bark from tree. The lower tusks

would have hid quite discretely under the trunk which extended from

the external naris, making it look less horrifying.

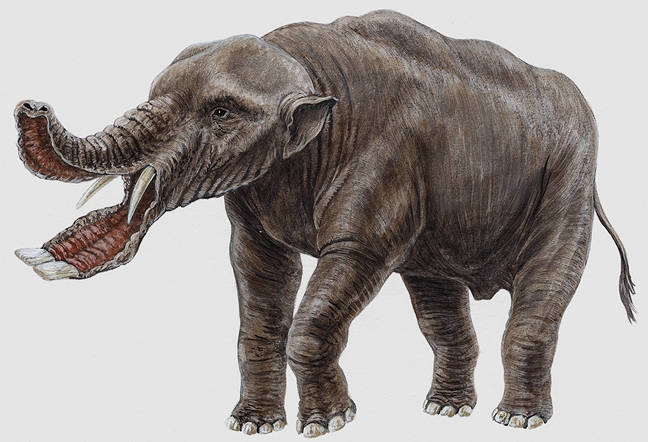

A reconstruction of Platybelodon

Platybelodon

is in the same family as Gomphotherium and is

not a direct ancestor of elephants. It lived about 20 – 8 million

years ago and retained all four tusks. The lower tusks

flattened out so the each tusk met and formed a sort of “shovel”

shape with a deep scoop at the end, which only developed in

adulthood. There is speculation about the use of it's tusks. It was

originally thought that it they used their “shovel” to scoop

through the mud to collect plants; a semi-aquatic lifestyle familiar

to Proboscideans. The two lower tusks end with a V-shaped sharpened

tip, analysis of the pattern of wear suggests they were used in a

scythe-like manner to cut down branches and to strip bark from trees.

Palaeontologists removed them from their presumed habitat of

lake-side bogs and place them in a more arboreal habitat. The shovel

tusks were an adaptation to a crowding niche, as with several genera

of Proboscidean in this area at the time, Platybeldon had to

specialise to survive.

A reconstruction of Gomphotherium

Another

key part of the future elephant physiology was put in place in

another of the elephants' direct ancestors, Gomphotherium,

living from 20 to 15 million years ago. They retained the four

tusks, with the lower tusks being slightly flattened, and show a

basic form of sequential tooth development. This is when, due to the

stresses caused by eating grasses containing silicon particles, a

tooth erupts from behind the existing teeth to replace the one which

had eroded at the front. The erupted tooth would be larger than the

previous ones, therefore allowing the jaw to continue to grow

throughout the animals life. Gomphotherium probably had three

teeth in each side of it's jaw, but later species had only one tooth

in each side of the jaw. Gomphotherium was a member of the

well travelled family Gomphothere, which includes the genera

Cuvieronius and Stegomastodon, some species of which

travelled as far as South America.

A sketch of American Mastodon Molars, my work

Mastodons

were, despite their common confusion with mammoths, very different

animals, Mastodons diverged from the line that would lead to

elephants after Phiomia, separating them from mammoths by

about 20 million years of evolution. The earliest Mastodons were the

Losodokodon which lived from 27 to 24 million years ago in

East Africa, later radiating throughout Europe, Asia and North

America. The most famous Mastodon species is the American Mastodon,

whose genus Mammut arrived in North America 11 million years

ago. The American Mastodon was around 2.7 metres at the shoulder,

small compared to the neighbouring Columbian Mammoth. It was quite

stocky with a deep chest and probably quite muscular. It's tusks were

up to 2.5 metres long in adult males and curved upwards and slightly

outwards, less elaborate than tusks of mammoth. The name Mastodon

means “breast tooth”, showing the lumpy nature of their molars.

Elephant and mammoth molars are relatively flat and ridged, whereas

mastodon molars have rounded cusps, which caused early naturalists to

speculate that they were terrifying beasts who caught prey with their

tusks. The reason each of these groups have significantly different

teeth is because they were used to eat different foods, none of these

animal foods. Mastodon teeth were used to crush leaves and twigs in

forests, whereas mammoths grazed grassland.

My drawing of a cave painting of a woolly mammoth

The

genus believed to be the ancestors of modern elephants and mammoths

is Primelephas. These creatures had four tusks,

though these were smaller than in Gomphotherium. This

is because Primelephus did not need them to shovel though the

mud, it had moved to a grassland habitat similar to modern elephants

on the savannah or mammoths on the steppe. This genus split into

three genera, Loxodonta (African elephants), Elephus (Asian

elephants) and Mammuthus (mammoths). Mammuthus belongs

to the Elephantidae family, making it as much of an elephant

as Loxodonta and Elephus.

Bibliography

Understanding

proboscidean evolution: a formidable task- Jeheskel

Shoshani www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0169534798014918

I

found the exhibition Mammoths: Ice Age Giants at the Natural History

Museum very informative, as well as the book of the same name by

Adrian Lister.

This was an entry to Rockwatch's Young Writer 2014 competition.